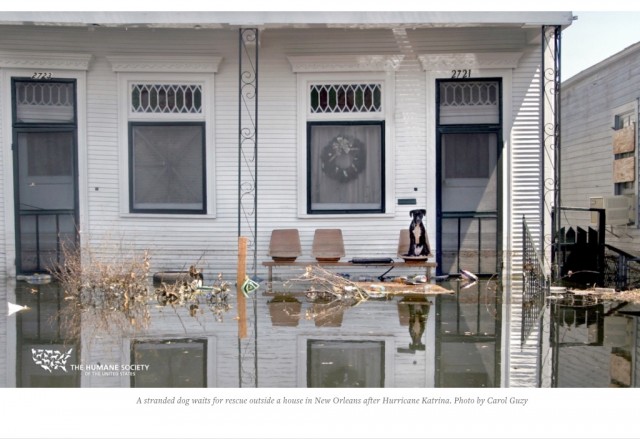

None of us can forget the televised images of the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. Among those images are video clips that showed people being evacuated from their homes in boats, their dogs trying to swim behind the boats, and the people crying and screaming at the dogs to go back. We remember images of abandoned dogs on rooftops, with no way to escape, no rescue in sight.

These are the images that drove us to New Orleans to help with the animal rescue. Our clinic sent a team of three–my daughter Amy, my technician Eddy Boisclair, and myself– down to Saint Bernard Parish to work alongside the ASPCA and the HSUS to help rescue and rehome animals that were abandoned during Hurricane Katrina.

When the people of New Orleans were evacuated, there were no provisions for evacuating pets. Rescue workers were under orders not to allow pets in the boats or buses. Still, thousands of people showed up at the evacuation points with their pets in tow, only to be refused. So they tied their pets to fences, or locked them into their homes, expecting to return after a few days.

When we arrived, rescue workers were breaking into homes as they became accessible when the floodwaters retreated. They searched for survivors, human and animal; many of these animals had been without food and fresh water for almost 3 weeks. Most of them were dead.

We were alerted one afternoon to some dogs requiring food and veterinary care in the only place in St-Bernard Parish that was open. It was a bar that had managed to get a generator, and was open for customers. I was greeted by a young man with a black lab dog who had “lost her bark.” She swam beside him through waist-deep water for 1/2 hour to get to higher ground when the levee broke. Since that day, she couldn’t bark.

When we asked how many dogs were there at the bar, and that needed help, the owner didn’t want to tell us. But finally he allowed us to go into the back room, where we found at least two dozen mattresses  crowded on the floor, each one occupied by someone with a dog or cat, and a plastic bag with their belongings. Most of these people were elderly. All of them had refused to evacuate because they could not bear to be separated from their pet.

crowded on the floor, each one occupied by someone with a dog or cat, and a plastic bag with their belongings. Most of these people were elderly. All of them had refused to evacuate because they could not bear to be separated from their pet.

Despite best efforts and countless hours, only a small number of the Katrina cats and dogs were ever reunited with their families. The vast majority of pets died in the floods. The majority of rescued pets were rehomed across the US and Canada.

There is no way to count, but we do know that many human deaths in the Hurricane Katrina tragedy could have been prevented if people had been allowed to evacuate with their pets. In response to this disaster, the Pets Evacuation and Transportation Standards Act, or PETS act, was passed by the United States congress in 2006. This law says that any state requesting assistance from FEMA (Federal Emergency Management Agency) must provide for the evacuation and safe shelter of pets.

On July 6 2013, we awoke to the horrific news of the devastation, explosions and fires caused by the train derailment in Lac Mégantic. My associate Dr. Tacium and I were called out to Lac Mégantic by the SPA de l’Estrie, which was on site to help with the rescue and reuniting of people with their pets.

When we arrived at the High School that served as the evacuation center, we found that in the far end of the school a s eparate area had been set up for the sheltering of families with pets. The Red Cross had set up cots, and the SPA had provided cages, dog and cat food, leashes, cat litter boxes, so that these people who had just lost everything could be co-sheltered with their pets. What a difference from what we had seen in New Orleans!

eparate area had been set up for the sheltering of families with pets. The Red Cross had set up cots, and the SPA had provided cages, dog and cat food, leashes, cat litter boxes, so that these people who had just lost everything could be co-sheltered with their pets. What a difference from what we had seen in New Orleans!

Hurricane Katrina showed us the necessity of animal rescue in the face of catastrophe. It was the storm that changed us.